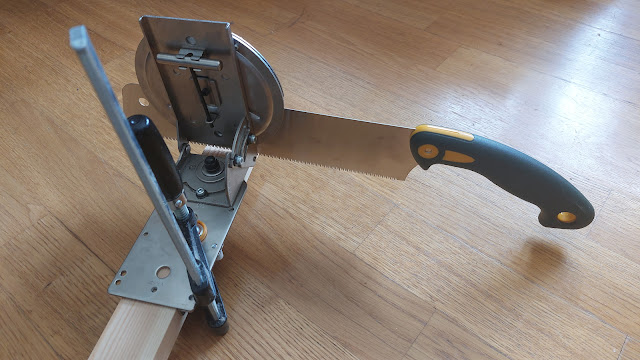

A follow up to discussing the Z-saw guide. This time I'm doing parallel cuts.

Here I needed to saw 6mm MDF and I expected it to be quite easy. It was not entirely without difficulties. I picked the smaller Z-saw guide and the mini 175 saw.

|

| After the cut. |

Using similar-sized 450x800 MDF boards on top of another, I could make a fence for moving the guide smoothly and check the 90-degree by aligning the top board as close as possible. This works only if the boards have been cut accurately enough in the factory!

However, my first cut didn't really succeed. From the ends, the piece has the correct measure, but something happened near the middle, resulting in a long curve, deviating about half a millimeter.

I had a few ideas of why it happened. The third one is the important one.

Firstly, I may have pulled the guide against the fence with too much force. After all, the fence was only clamped from the ends. This couldn't really happen inwards, but perhaps vertically, just enough to disturb the guide.

Secondly, sawing ahead of the guide can result the blade veering just a little bit, and from that moment on the board itself can force the saw into misalignment that's neither easy to see or correct. If everything else is right, speed in itself shouldn't matter all that much.

|

| Left: wrong. Right: right. |

Thirdly, and most importantly, I sawed with a too steep angle. Using a lower angle should create more surface between the saw and the guide. This also makes the cut in the board act as a better guide. The saw point where the "decision" is made is closer to the guide midpoint.

For the later cuts, I tried to keep the angle low, adopted a routine for moving the guide, sawing as much as by ear as by eye. I tried to hold the guide in place, only pulling it gently and checking it is firmly against the fence.

It is important to have a good, comfortable position from where you can also see the saw alignment. The blade shouldn't bend at all against the guide.

The later cuts were about as perfect as I could hope for.

|

| Measure and mark, use the dummy plane, dummy. |

Repeats, as I've already observed, are not very simple to do with these guides.

Ideally, there would be a jig for making similar cuts without measuring each piece separately. But for that I'd have to build a rather large jig.

Fortunately I think it is enough for most cases to do an accurate marking and measurement, and use the dummy blade to simulate the cut. You have to choose how the dummy is placed in relation to the marked lines, and be consistent with this choice.

Errors might compound if pieces are sawed off from the same board, and the new measure is each time marked from the previous cut. The pieces could end up correct width but no longer precisely rectangular. This compounding should not happen if the fence can enforce the 90 degree angle for each cut.

Drawing all lines for all cuts beforehand isn't viable, as the blade thickness is difficult to factor in.

With these techniques I began to make a 38x220x89mm box using MDF slices from 800x450 boards I ordered. (The box is intended to fit a 19 inch standard rack, taking two rack units.)

|

| Spot the mistake |

The plan for sawing the material was made in Librecad. This doesn't take into account the saw thickness, so it is just an approximation of whether the material is enough for a box.

After the shaky start described above, the rest of the wall pieces were accurate.

I glued the box together using four Wolfcraft (that brand again) corner clamps and two Cocraft clamps. As the wood glue doesn't dry instantly, there's some time to adjust the corners. Much like with artists' oil paints, the slow drying is a feature, not a bug.

The corner clamps are more for keeping the pieces up and do not itself produce an accurate position.

|

| Corner clamped |

Although the Cocraft clamps only give a gentle pressure, without them the box would fall apart.

The bottom was then glued and held together with six small clamps.

I was initially well pleased with the box. But, considering the box was intended to fit a rack mount, I had made a crucial mistake.

For some reason what was meant to be the outer dimension (438) had become the inner dimension and the box ended up being 450mm wide instead of 438. This mistake was made early and I had ordered the MDF material already in wrong size.

|

| Corner clamped and glued |

What's even more unfortunate is that I'd already added reinforcing pieces to the inner corners of the box.

I pondered if I should simply build another box, but I couldn't foresee any use for the wrong sized one. The Z-saw guide and the saw came to the rescue. I cut away the ends from side and yanked them off using a clamp as leverage. Then I cut 3mm MDF to size and glued them to the ends.

The end result is not 438mm, and not as clean as the original box, but at least I can continue prototyping. Some day.