I've not kept a good track of where I have picked up a particular advice. I have read books from Gideon Ståhlberg, Fred Reinfeld's The Complete Chess Player, and a few glances at Max Euwe and Keres & Kotov and other books. Plus whatever I found on the internet at that time.

More recent theory I found from Ristoja & Ristoja's chess books from the 1980s and I've had a brief look at 2000s theory from Mika Karttunen. Turns out many things that were still considered iron rules in 1960s books are already in the 1980s considered far less imperative: a chess position is now considered as a dynamic situation.

Still, I've liked the idea that theory can be the end result rather than a starting point. This is another simplification, but often what you find in books is a summation gained from a long career, an insight that resulted from a huge amount of playing and perhaps teaching chess. The road to this expertise is often forgotten, and hence we still have books that first show how the horsie moves and then goes straight into the subtleties of a variation of a Sicilian opening.

After the initial rush to books, playing a lot of puzzles and gaining playing hours were the most important thing for improving. Chess skill advances as any skill does, a combination of playing a lot, doing exercises and acquiring some "theory" and perhaps some goal-setting suitable for one's skill level.

"Exercises" might mean playing huge amounts of puzzles or concentrating on some particular opening or game style, or attempt at an analysis. Also, fast games might be exercises for slower games, and vice versa.

The middlegame is the ground for the most vaguest theory. There are just too many potential situations and patterns to be identified and addressed to make into iron rules.

Piece movement (very early notes)

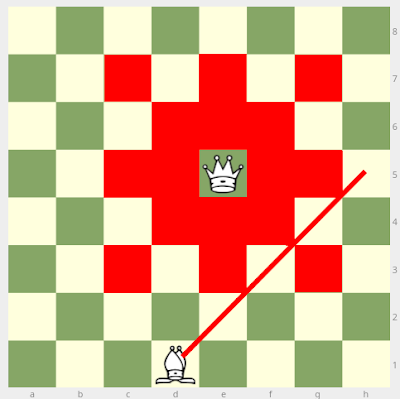

Pieces can be visualized as both the piece and the area it threatens. Rooks and Bishops form perpendicular and diagonal crosses. A Queen forms both.

In addition to the 8 directions, it may help to see the Queen as carrying a star-shaped zone. This is useful when forming certain types of checkmates.

Furthermore, the pieces can be thought to "paint" the threat areas they can reach through one move, creating a sort of secondary zone of motion/threat.

This way it would be already possible to see moves ahead without having to logically examine the repercussions of every possible move as in a decision tree.

The above shows the squares the knight could threaten after 1 move (circled squares). I felt like highlighting the "more safe" squares: these are squares the knight can't threaten even in 2 moves. (There's one more, in the corner where the black king is)

Instead of the one-step, two-step motion, or "L shape", the knight may be better visualized as series of 2,1 or 1,2 "vectors".

Other pieces may be visualized with the knight zone around them, to help assess how to reach that piece (often avoiding a fork). "Safe" locations are at (2,2), (3,2) and (3,0) relative to the knight, and these are also quite easy to visualize as a box.

Just as an example, analyzing some of the "Knight laws". A lot of this is re-stating the same thing in different ways.

- The knight always threatens squares of other colors than the square it is in.

- Pieces on different colored squares cannot be directly forked by the knight.

- If the knight moves, it will never threaten any of the same squares as previously.

- If the knight moves, it will threaten the square it was in.

- The knight takes 2 moves to threaten a directly adjacent square (not diagonally adjacent)

- After moving the knight, a square it might threaten, can often (but not always) be threatened from an alternative square .

- The knight threatens less squares from edge/corner, and is more susceptible to imprisonment there. Still, good ideas based on a knight at the edge ought not be dismissed.

- To avoid being threatened by a knight, a piece can be positioned next to it.

- Other easy to visualize safe spots are ±2,2 ±3,2 and ±3,0 locations relative to the knight.

- Be mindful of positioning pieces in ±0,2 ±2,0 ±0,4 ±4,0 relation to the knight.

- To avoid getting forked, pieces may be put to different-colored squares.

- A bishop can quite effectively limit knight motion from the ±3,0 and ±0,3

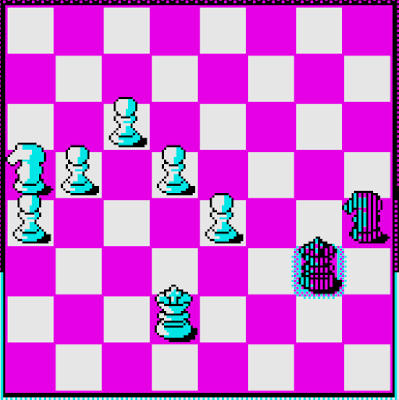

Looking the chessboard naively, it is a horizontal-vertical "rook-space", but for the Knight it opens up differently:

|

| A slice of knight's "space" within the board. |

|

| Another slice of Knight's "space" within the board. |

Later note: There's not much support for this kind of visualization in any of the books I've read, and I'm unsure about it myself. I felt it was interesting at the start, but truth be told much of this thinking isn't active during the games. It more likely develops through playing a huge amount of games and puzzles.

Openings:

There was a phase when I tried to learn some interesting-sounding openings by heart, but it turned out to be not too helpful. Again, I now think it is better to remember openings through playing a lot of games while sticking to as few openings as possible.

2023 note: I stick to e4 with white, and study the more likely openings that result from this choice. Black responses to different white openings need to be studied also.

At Lichess low level online blitz games, I soon started to recognize Italian Game and the Parham Attack and the blatant traps inherent in them. After this it becomes a good idea to find out the good moves for responding to these routine threats and building up a better defense.

I've come across an idea that beginners do not benefit from knowing named openings all that much. Any advantage gained from a correctly memorized but poorly understood opening may melt easily after a few moves anyway. Knowing that Sicilian is the best black response at master level, might lead to a poor play for the beginner player.

Instead of learning openings by rote, rules of thumb may be useful for improving the opening:

From Reinfeld:

Primary idea:

- Create viable attack positions through acquiring control over center

- Ensure defense and protection of all forward-moving pieces

- Refrain from defining the pawn lines too early

- Refrain from castling too early

Pitfalls:

- Immediate holes in defense

- Inconsistent approach (?)

- Too much time spent in achieving a specific tactical idea (=lost tempo)

- Develop "All", ideally by moving pieces (non-pawns) only once.

- Pawn moves are not development, ideally only 1-2 pawn moves in an opening.

- Pawnless advance does not work either

- Formula: Developed Pieces = Tempo.

- Compound moves. Moves that both develop and force opponents to waste moves. ("Don't just develop, develop and threat!")

- In a closed game (d-game) the development may be slower and with more pawn movements.

- Flank pawns are a waste of time in an open game (e-game)

- Never play to win pawns when development is unfinished (exceptions...)

- Center pawn should always be taken if not too dangerous.

- Exchanges and gain of tempo, these are related.

- It is a mistake to move a piece several times to exchange it for a non-moved piece.

- Liquidation = "radical" exchanges that relieve tension in the center (if necessary).

Some other ideas to observe during the opening:

- Don't move the queen early on unless it's really called for (traps, regaining a pawn)

- Be wary of moving the f-pawn at the very beginning (not often compatible with kingside castling, may also block the knight)

- Knights before bishops, but also be wary of blocking your bishops.

- Observe the potential threat from bishop to h2 (h7) pawn and devise the castling accordingly.

- Likewise, see if the Greek Gift can be realized against the enemy King-side fort.

- Possibilities for variations of the Fried Liver attack or other types of knight/bishop double attacks, but it's almost never worth it to lose both just to gain a rook and a pawn.

- 2023: I almost never look into "Fried Liver"

- Possibility of removing opponent castling through queen exchange

- However, without queens the castling is not that meaningful

- Preventing or postponing the opponent from castling

Especially older books sometimes suggest playing a lot of e4-games before moving to d4 games. Not sure why, but to me it's seemed that a Ruy Lopez, although very deep, results in a more "normal" chess than other openings.

The "control of the center" seems like an obvious idea but at least to me it is a difficult concept to grasp. It's easy enough to observe the opening pawn exchanges and the building tension around them, and it is clearly a bid to control the center. But what is to control the center? Having a bunch of your own pieces cluttering the center and blocking the diagonals is often not that helpful.

But I've seen that if the opponent has a well protected pawn or two at the center, and you don't, this often spells disaster. Similarly, if the center is empty, a vicious bishop-pair can decide the game.

Middlegame:

I have little to say about middlegame. Tactics still seem to dominate this area, together with spotting opportunities, either plain unprotected material, weakly positioned pieces or overburdened defense. These are what Reinfeld calls "landmarks", a motive for planning forward.

Current theory sees that these kind of "iron rules" are never too absolute. They might be considered as material for learning and reflection. (The advantage may be other than simply material.)

Keres & Kotov felt games can be characterized by castling-sides but also the openness or closedness of the center. This would give, roughly, a matrix of 12 "game variants" if non-castling is considered. Other literature has simply suggested a division between open and closed games.

Later note: The pawn advance isn't an end in itself, the point is to open a line on the opponent's castled side.

At one point, playing an enormous amount of puzzles improved my middlegame tactics quite a lot. Recently, playing "puzzle storm" at Lichess was also helpful at activating the eyes and the brain to recognize opportunities and what to do with them.

2023: Puzzles helped greatly in recognizing tactical opportunities, but they don't help much in creating the opportunities in the first place.

"Planning" largely comes into play here, but this is still a grey area to me.

Tactics

Pawn structure becomes especially important in the endgame. Envision the endgame pawn situation already in the middlegame.

Some examples of advantages Euwe mentions: Material, Rank, Mobility, Spatial advantage, Sustained pawn formation, Safe position for the king, Tempo, Initiative of attack, Knight on a strong square, Bishop pair...

Exaggerating Euwe's ideas, the situation in a Chess game might be seen like this:

These are just examples of opportunities of exchanging one thing for another. Sometimes, in beginner games a really fast attack might bring rewards, but when it fails, it often marks a turning point and the attacker loses. Almost everything else was exchanged in order to make that one attack possible.

Controlled center and a bishop pair is apparently a good combination. A bishop pair without the center may not be such a superior strategic advantage. Be mindful of especially queen/bishops positioning directing towards/through center.

Of course, overall material value of pieces is still a good indicator of your standing, but an immobile piece is a non-piece at that point of time. Other issues can subtly undermine your pieces' apparent material value.

- Forcing desirable opponent moves

- Breaking the opponent's pawn line (and/or creating double pawns)

- Opening a beneficial line, rank or diagonal for yourself

- Creating disadvantageous squares (color, or otherwise)

- Removing a blockade whereas creating one for the opponent

- Removing opponent's bishop pair

- Preventing opponent from castling

- Breaking the castling

To summarize, a sacrifice is not only made just to be able to win a more valuable enemy piece a few moves ahead, but different advantages can be "bought" or "borrowed" with it.

Vice versa, be very doubtful of something that looks like an offered piece.

Later reflection: This Euwe idea made originally a big impression on me, as if some revelation about Chess had been opened up. I now have to accept it hasn't made a huge impact on how I play. Perhaps the biggest takeaway is that although good advice and rules exist for strategically and tactically sound game, at a given moment "you can't do everything". You often have to disregard some aspect in order to gain initiative or tempo, and pay the price later. If you don't, your opponent might.

Thoughts on "strategy"

Most initial learning seems to concern tactics. I can't say I understand strategy much as yet.

"While [computers] are perfect tacticians [...] computers lack any sense of chess strategy. Fairly good players who understand that fact can direct the game into long-range strategic channels [...]" (Dreyfus and Dreyfus, 1986, 113.)

The chess literature isn't always that clear what kind of thinking belongs to strategy. To some, topics such as weak/strong squares and pawn structure is already a strategy topic rather than tactics. "Improving position in piecemeal fashion" would then be strategy.

As a beginner, I easily disregarded pawns. Promotion was something of a happy accident rather than a design. This also meant if my opening resulted in a loss of few pawns, I was okay with it. Now I am paying more attention to pawns and I also see a lot of the openings build-up around pawns and threatening and defending them. Later in the game, planning might be based on simply eroding the opponent's pawns before endgame.

More recent theory does not recommend having one major plan, but shift it according to how the game develops, dynamically. To me this makes the notion of a "plan" strange, but clearly it's not a healthy sign if you find yourself moving pieces aimlessly.

Again I'm reminded of Fred Reinfeld's "landmarks", which experienced chess players learn to see at a glance:

- Loose pieces suggest forks.

- Loose pawns are a weak spot.

- Overburdened defense is a weakness.

Ståhlberg: In master-level play, the one who loses a pawn with no gained advantage, will lose the game.

Ristoja: (paraphrasing only slightly): Only the beginner aims to checkmate. The mature chess player plays the opening to have a good middlegame, then plays the middlegame to have a good endgame. The threat of a mate is often a more important tool than a premature attempt to win.

Reinfeld also says: the player who is ahead materially, seeks to exchange Queens, to simplify the game. The one who is behind, relies on creating confusion, traps and complications.

Karttunen: (again, paraphrasing) After exchanging queens, the castles are not quite as meaningful. The kings might even be better at the center after the exchange has happened. The player whose castle is broken or about to be broken, might want to seek to exchange queens, despite everything else.

Endgame:

The endgame with very few pieces becomes again a terrain for more discrete knowledge, such as whether and how to checkmates with certain combinations of pieces.

I will not list checkmate patterns and piece combinations for the endgame, however they simply need to be known as the more sophisticated games are usually decided here. When the clock is running out, it would be better to have a good grasp of how to checkmate quickly with a queen or a rook without stalemating.

This advice is more about the point of transition from mid-game to endgame:

- Pawns, preferably on non-castled side are useful (already the threat of promotion is a powerful tool)

- Two bishops are often more valuable than two knights or knight+bishop

- Two rooks can be more valuable than a queen

- Queen endgame: one pawn advantage is not enough. A strong, free pawn is needed.

- Visualize the pawn square rule for promotion

Random notes

"When threatened, find the best way to do nothing"

If the castle seems to hold, why alter it? Use the tempo to develop an attack instead.

The most important rule is... "YOU BELONG HERE!"